Phantasmagoria

Introduction

Phantasmagoria was an immersive theatrical entertainment that emerged in the late 18th Century. Phantasmagoria plunged audiences into complete darkness, then used a precursor to the movie projector called a magic lantern to terrorize them with horror-themed images. The most famous purveyor of Phantasmagoria was physicist and balloonist, Étienne-Gaspard Robert, who went by the stage name Robertson. Robertson took the Phantasmagoria beyond scary projections in a dark room, and evolved it into a fully experiential entertainment.

The Experience of Robertson’s Phantasmagoria

Jan, 1799. Paris, France. Imagine yourself living in that time. Ghosts, spirits and other horror-rich subjects are in the air. You may have already read one of the great protostars of Gothic fiction, like The Castle of Otranto or The Old English Barron. You may have even indulged in the twisted tales of Marquis de Sade. You are certainly aware of politics. Only a decade ago, revolutionaries stormed the Bastille and kicked off the French Revolution. A few years later, the Reign of Terror brought massacres, public executions and thousands dying in prison.

Imagine yourself walking a Paris street one afternoon. You come upon a poster depicting a witch raising a man from the dead, and promising “…apparitions of Spectres, Phantoms and Revenants…”

This looks like an enticing evening’s entertainment, so you make your way to the location indicated on the poster, the Convent des Capucines, ‘one of the lasting models of “pure Gothic architecture”’

Upon arriving at the convent, you are greeted by a man dressed entirely in black, who calls himself Robertson. Robertson invites you in and leads you through a labyrinth of dark passages, littered with crumbling statues, alters and smashed tombstones. The place appears to have been deserted and left to rot. You are aware that there is history here. The nuns who inhabited this convent were expelled during the Revolution.

Soon, Robertson has led you so deep into the twisting passages, you feel like you are more distant from the city outside than you actually are. Now, you pass by a series of eerie Danse Macabre paintings, “...images of citizens being led away by skeletons…” reminding you that death is never far from your side.

Now, the tone of your journey changes. Robertson leads you into a well-lit lab he calls the cabinet du physique. Here, he encourages you to behold rational, scientific experiments revealing the mysteries of the universe, but still reminding you of your own mortality and fragility within that universe. Robertson activates a galvanic experiment and temporarily reanimates a dead frog; Can the man bring the dead back to life? Next, he steps to a microscope and invites you to view a mere flea, now magnified into a hunched and terrifying monster. Robertson shows off other oddities, anamorphic memento mori, paintings that only reveal their true nature when viewed at specific angles, or through special warper mirrors. These too strike a balance. They demonstrate the unseen in the universe, but they are repeatable, thus must be based on modern, scientific principles.

Suddenly, an eerie dirge fills the cabinet du physique, a sound so strange and other-worldly, it may emanate from some spirit or demon. This sound grows in volume, becoming more and more disturbing.

Robertson now leads you to a door, intricately carved with Egyptian hieroglyphs. Your mind recalls that, at this very moment, Napoleon is stranded in Egypt. Is there some connection here? Robertson opens the mysterious door onto a crypt-like chapel, draped in thick black curtains, and lit only with one dim lamp. He bids you enter and be seated in one of the available pews. Then, ominously, he produces a key and locks the door by which you entered. There is no escape.

Robertson moves to one end of the chapel and addresses the gathering. His speech tours through literary and scientific references; Racine, Sterne, Voltaire, Rousseau and Schiller. He claims that what he will show you is nothing more than an optical illusion.

Then, whoosh! The dim lamp extinguishes itself, plunging the chapel into pitch-black darkness. Gradually, the sounds of rain and thunder blend with the ethereal strains you heard upon entering this infernal space.

Now, far off in the complete darkness, you perceive a small bit of light. The light grows, until it takes shape as a figure coming toward you. The figure is a scythe-wielding skeleton charging, ready to cut you down. The figure is Death itself.

French engraving depicting Robertson's show at the Couvent des Capucines. Note Robertson projecting from behind the screen.

Thus begins your horrifying journey into the world of the spirits. From here, Robertson shows many other horrors. The hated face of the Reign of Terror, Robespierre, rises from the grave. Next, the horrifying image of the Bleeding Nun, from the Gothic novel, The Monk. Then, the great, snake-haired medusa. But he periodically tempers your fear, showing more beloved deceased figures like the writers and philosophers Voltaire and Rousseau.

You certainly leave Robertson’s Phantasmagoria impressed. And you are not alone. The famous gastronome Grimod de la Reyniere commented:

“The illusion is certainly complete. The total darkness of the location of the scene, the choice of the figures, the astonishing magic of their truly terrifying gradation, the prestige that surrounds them, all come together to strike your imagination and to take over all your observational senses…”

How Robertson’s Phantasmagoria Worked

Étienne-Gaspard Robert was not the first person to create a Phantasmagoria horror show. It seems clear that he lifted a lot of his act from a well-known, but mysterious contemporary named Paul Philidor . But Robertson innovated the form, by improving on existing technologies and bringing numerous experiential elements together into a single, unified journey.

The Setting

Robertson set his Phantasmagoria in the Convent du Capucines. Abandoned since the Revolution, and in disrepair, this setting would remind audiences of the death and upheaval in recent years. At the same time, the deteriorated statues, alters and gravestones would lend an added air of gloom. Setting his show in the convent was analogous to staging Hamlet in a real Danish castle. Magician Noah Levine hosts “Magic After Hours” in Tannen’s Magic. Hidden away in a nondescript Manhattan office building, Tannen’s is the oldest magic shop in the US and long-time secret club to magicians far and wide. The locations themselves underline the themes of the stories they house.

The Queue

When you visit Disneyland, and ride the Haunted Mansion ride, the queue itself is loaded with story. You pass gravestones etched with humorous quips. You enter the famous haunted “stretching room,” which is actually an ingeniously-disguised elevator taking you down to the main ride. You pass by a series of haunted busts, whose eyes appear to follow you. All of this sets the tone, and primes your mind for the haunts ahead. By the time you get on the actual ride, you have already entered the world of the ride, and you know what tone to expect.

Robertson was employing very similar techniques, bringing the audience into the world of the story long before the show started. By leading the audience through a labyrinth of passages, he created the sense that the audience was descending into a nether world and possibly getting lost there forever. He then switched gears and led the audience into a well-lit laboratory. He showed off experiments and hidden wonders of the natural world, but in a way that supported the overall themes of death and the unknown. When he used electricity to activate a dead frog’s limbs, or a microscope to show bacteria and fleas close up, he “...revealed how much lay outside of the human optical range.” He raised questions in the audience’s mind about how much they actually know about the world, but he did it through the scientific lens so popular at the time.

The Main Show

But then Robertson switched gears again, and filled the well-lit lab with the unexplained, otherworldly sounds of the glass harmonica. This instrument is made up of rotating glass bowls. A musician plays the glass harmonica by running their fingers over the bowls, creating an eerie music that easily evokes the mysterious.

Finally, Robertson led the audience into a long room lit only with a single, dim lamp. Darkness is always disorienting. Here, the audience literally steps into the unknown.

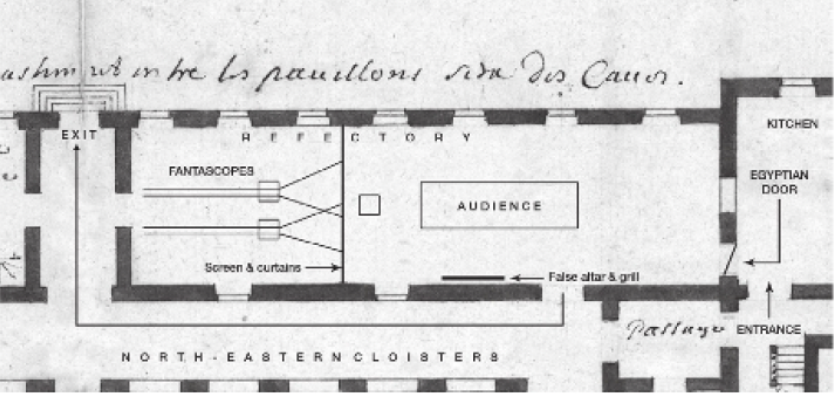

Robertson’s pre-show speech blended allusions to scientific writers and topics, with literary images like “...life occurring between two impenetrable veils...” Then, directly after his speech, he dramatically plunged the audience into darkness, increasing the tension. Robertson gave his speech before what appeared to be a wall. But when he extinguished the lights, he ducked behind this wall and revealed it to be a semi-transparent screen. Behind the screen, Robertson lit up the device that brought his phantoms to life; the magic lantern.

Robertson’s magic lantern

A precursor to the film projector, the magic lantern shined light through painted slides, to project images onto screens or walls. Magic lanterns had been used for years, even in other horror-filled Phantasmagoria shows. But Robertson patented his own version of the device, called the Fantascope, with a number of improvements that added to his show’s effect. The Fantascope was one of the first magic lanterns to use an Argand lamp, much brighter than the common light sources used in other magic lanterns of the time. This allowed Robertson’s images to be brighter and more striking. Robertson also placed his Fantascope on rails, so that he could move it in real time. He started with the Fantascope close to his screen, making the image very small. As he rolled the Fantascope back away from the screen, the image grew larger and larger. To the audience on the other side of the screen, the effect was opposite: a figure of Death, say, appearing far in the distance, then coming closer and closer, growing in size until it was right on top of them.

The Legacy

Robertson took the Phantasmagoria beyond scary projections in a dark room, and evolved it into a fully experiential entertainment. His innovations in priming an audience are reminiscent of techniques used in magic shows, theme parks and immersive theatre. His selection of venue to underline the themes of his show, is echoed in the site-specific theatre movement of the 20th Century. By merging the macabre and the pseudo-scientific, he played into the audience’s popular views of themselves as enlightened, rational beings, rather than superstitious rubes, while also playing on their wonder and fear at the hidden machinery of the universe science was revealing day after day; a theme that would permeate spiritualism throughout the next century. Finally, by putting his magic lantern in motion, Robertson truly brought his horrors to life, and helped transform the device from a static slide projector into a motion picture projector.

Bibliography

Barber, Theodore “Phantasmagorical Wonders: The Magic Lantern Ghost Show in Nineteenth-Century America ” Film History, 1989, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1989), pp. 75

Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glass_harmonica. Accessed 4 December 2021.

Levine, Noah. Magic After Hours. http://www.magicafterhours.com. Accessed 4 December 2021.

Mannoni, Laurent and Brewster, Ben “The Phantasmagoria” Film History, 1996, Vol. 8, No. 4, International Trends in Film Studies (1996), pp. 405

Jones, David J. Gothic Machine Textualities, Pre-cinematic Media and Film in Popular Visual Culture, 1670-1910. Cardiff, University of Wales Press, 2011, pp. 179